New Adapter Lets Photographers Use Instax Film in Vintage Kodak Cameras

In 2016, photographer and filmmaker Josh Gladstone designed a way to use Fujifilm Instax film in vintage Kodak cameras. It was very hands-on and had some limitations. Eight years later, Gladstone is back with a much more elegant 3D-printed solution.

“I really wanted to make a 3D-printed adapter that could take Instax cartridges directly,” Gladstone explains. “I made a few attempts, some of which were pretty wild.” Some of Gladstone’s efforts included a motor-driven holder with rollers, but there were reliability issues, so he put the project on the back burner for a few years.

Fast forward to today, and Gladstone has a “much better” Bambu Lab P1S 3D printer, and the time was right to give it another shot.

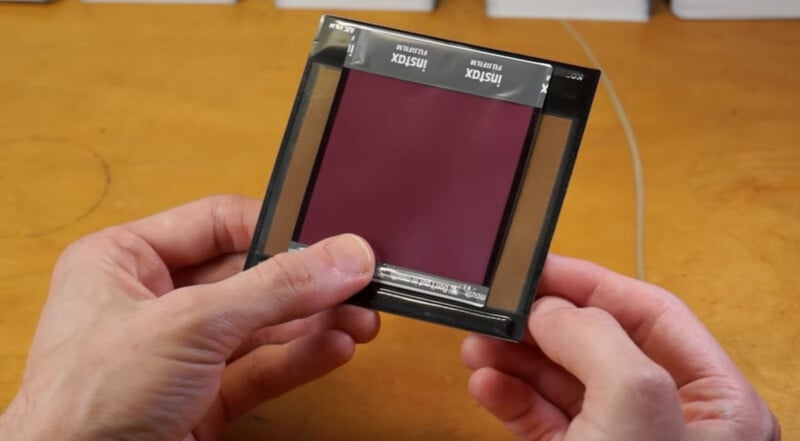

“After a lot of trial and error, I finally have a reliable, working, 3D-printed Instax adapter for some vintage Kodak instant cameras,” Gladstone explains.

Before diving into his new adapter, it’s worth venturing back in time to learn a bit more about Kodak’s instant cameras of the mid-1970s, which were meant to compete against the very popular Polaroid instant cameras of the era, some of which live on to this very day.

Although Kodak exposed its instant film differently than Polaroid, the latter was not keen to have competition and sued for patent infringement. Polaroid won the lawsuit, and Kodak’s instant cameras went the way of the dodo bird in 1985.

However, the echoes of Kodak’s instant cameras are felt today. As Gladstone points out, something fascinating happened between Kodak entering and exiting the instant camera space. Fujifilm decided to get involved, and licensed technology from Kodak.

Because Kodak eventually lost its lawsuit against Polaroid, this put Fujifilm in an interesting spot, and ultimately, Polaroid and Fujifilm reached an agreement to allow Fujifilm to continue to sell its Kodak-derived instant camera products in Japan. Eventually, Fujifilm adopted the Instax brand, which is an absolute smash success even today.

Fujifilm Instax’s Kodak roots are a driving force behind Gladstone’s project, as the shared foundational technology ensures that the different systems are compatible, even if a bit of finagling is required.

Returning to Kodak vintage cameras, there were two types: manual crank-operated and automatic ejection models. Although an automatic ejection instant camera is the norm today, Gladstone notes that this type of Kodak camera doesn’t age well and routinely fails. However, the crank-operated cameras can survive the test of time, so he recommends only working with these.

Another consideration is film speed. The original Kodak instant cameras in the 1970s used ISO 160 film. In the 1980s, before Polaroid ended Kodak’s instant camera hopes and dreams, Kodak released a Kodamatic film, also known as Trimprint, that featured an ISO 320 speed. As for modern Instax film, it’s ISO 800.

Unsurprisingly, there will be overexposure issues if a photographer puts Instax film into an old Kodak camera, whether it is an original model or one made for the faster Kodamatic film. However, the Kodak instant cameras include an exposure compensation dial, so users can darken the exposure to compensate for the different film speeds.

Beyond the differences in film speed, photographers must also consider differences in framing when using the Instax adapter for Kodak instant cameras. Kodak instant cameras use larger image areas than modern Fujifilm Instax cameras, so Instax film does not take full advantage of the Kodak’s focal plane.

However, the Instax film adapter centers the film, so the issue is relatively straightforward to overcome. As long as the user consistently loads the film, they can learn how the Kodak camera’s viewfinder framing corresponds to the Instax film. It will take a bit of getting used to, though.

“You need to aim a little bit above where you normally would, especially for subjects that are relatively close,” Gladstone says. “Or you’re going to cut people’s heads off. Photographically.”

Despite these minor caveats, Gladstone’s new DIY project will breathe new life into vintage Kodak instant cameras, allowing photographers to have fun new experiences with 50-year-old cameras. Instax film is ubiquitous and comes in various styles, so there are plenty of exciting possibilities. All the required 3D printing files are available for free on Thingiverse, and the springs Gladstone used are available on Amazon for $10. Gladstone writes of the springs: “For the main spring in the adapter, I used a 0.6 x 7 x 20mm 10 lap spring that was then stretched to be about 35 or 40mm. For the spring back plate adapter, I used a 0.6 x 7 x 10mm 6 lap spring that I cut in half and used both halves in the adapter.”

By the way, Gladstone’s current adapter is just for Instax Square film, but he has worked on a special adapter for Instax Mini. There have been some consistency and reliability issues with the Mini adapter, so he isn’t releasing yet — but it’s in development.

Beyond this fun Kodak instant camera project Gladstone has been working on for years, he has also done some fascinating work with volumetric video. PetaPixel featured his video projects a couple of times last year.

Image credits: Josh Gladstone