Adobe’s Terms of Use Controversy Provided an Opportunity to Improve

![]()

Less than two weeks after significant outrage concerning Adobe’s Terms of Use, fueled in part by poor communication, a lack of trust, and good old-fashioned misinformation, Adobe has delivered its promised revised Terms of Use, complete with new explainer text and assurances.

PetaPixel chatted with Adobe’s Scott Belsky ahead of the company publishing its new Terms of Use, with Belsky explaining that while much of the uproar could have been avoided by the company being more careful and precise with its communications, the company has used the experience to reconsider its entire Terms of Use.

“People were justifiably concerned,” Belsky says of users’ worries while reiterating that some of the greatest fears about Adobe using its users’ content to train Firefly or stealing people’s work were unfounded.

Adobe believes it came up short by not effectively communicating its Terms of Use and addressing potential concerns before they spiraled into a full-blown public relations disaster. Although Adobe’s Terms of Use have long been in line with many competing applications, Belsky admits that the company failed to adapt to changing customer expectations and concerns, something it believes it has done with its revised Terms of Use.

A significant way Adobe is doing this is by providing context and explanations for the parts of the Terms of Use that have been the most controversial and confusing. For example, companies must have limited licenses to user content to provide certain services and features, like having a license to show a thumbnail. This is standard fare in a Terms of Use or service, but without any context, it can sound scary or seem like Adobe is claiming some form of ownership over user content — which it isn’t.

Further, while some customer data is used to train certain pre-release and beta features, which are opt-in services, Adobe has been adamant that it has not and does not train generative AI with user content. The company has said it numerous times before and is taking the opportunity to repeat it.

“This license does not give us permission to train generative AI models with your or your customers’ content. We don’t train generative AI models on your or your customers’ content unless you’ve submitted the content to the Adobe Stock marketplace,” Adobe writes in one of its new “explainer” sections of the updated Terms of Use.

Another issue many brought up a couple of weeks ago is that it wasn’t apparent if Adobe claimed ownership over user content in any capacity. Adobe requires limited licenses to provide certain services, like publishing content on Behance, but this license does not transfer any ownership of user content to Adobe.

“You own your content,” Adobe explains. “But in order to use our products and services, we need you to give us permission to use your content when stored or processed in the our cloud. This permission is called a license.”

“This license allows us to provide our products and services to you, like if you want to share your content or publish your content on Behance,” Adobe continues. “Because it’s your content — not ours.”

In a later section, Adobe has written new terms that outline specific actions that Adobe does not do.

“We will not (and cannot) grand a sublicense to a third party that is greater than the rights you give us,” Adobe writes. “Under this clause 4.3(A), we do not have the right to, and will not, use your Content to market or promote Adobe.”

“We will not use these rights to train generative AI models on your Content and will not use the sublicense rights to have ayone else train generative Ai models on your Content, except at your specific request (like you asking us to train a custom model on your Content).”

It is unusual to see an explicit “Company X does not do this” proclamation in a legally binding document, like a Terms of Use, but Adobe believes it is important to ensure that there is no ambiguity or space for people to be confused or worried about their files being used to train generative AI. This is a relatively new concern and one that Adobe hadn’t given enough consideration to before.

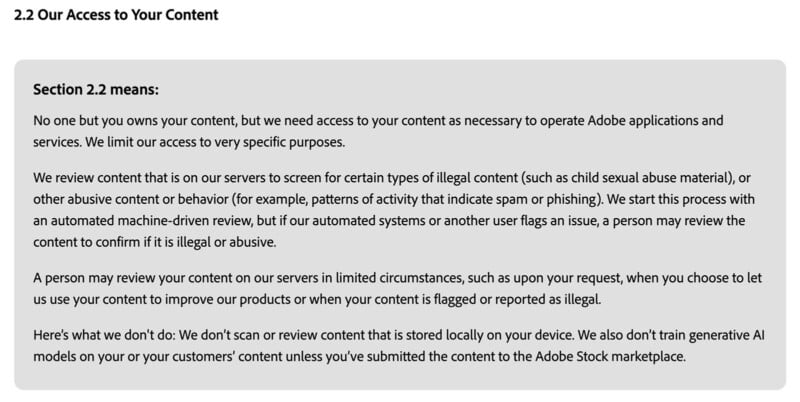

Privacy is another major topic for users, and for good reason. Adobe says that it “may review content that is on our servers to screen for certain types of illegal content (such as child sexual abuse material) or other abusive content or behavior (for example, patterns of activity that indicate spam or phishing).” While these automated systems should not flag NDA content, people concerned about their privacy must understand the potential risks that come with utilizing cloud services.

In this new section of the Terms of Use, Adobe explains that the process is automated but may be elevated to human review if content put onto Adobe’s servers gets flagged by the machine-driven review.

“Here’s what we don’t do: We don’t scan or review content that is stored locally on your device. We also don’t train generative AI models on your or your customers’ content unless you’ve submitted the content to the Adobe Stock marketplace,” Adobe adds.

While Belsky says that internally, Adobe employees knew what the company did or didn’t do with user content, the company is grateful for the opportunity to improve its approach to communication and transparency. Belsky describes the Terms of Use situation as “painful,” and he has personally been subject to a lot of abuse. Still, he believes everyone will benefit from the more transparent Terms of Use, including potential users of other companies who may find that they have space to improve their Terms of Use, too.

Adobe hopes people will see that its efforts to improve are sincere and that its users will find the revised Terms of Use helpful.

The company’s more significant efforts toward improved communication and rebuilding trust with its users will be a much longer-term endeavor that demands a consistent, reliable pattern.

That said, this is a good first step. It’s high time that Terms of Use don’t require a law degree to understand and that companies are open about not just what is in the Terms of Use, but why terms are there. Ultimately, it is up to individual users to decide what they are okay with, but that requires them to easily understand precisely what a company is asking them to agree to in the first place.